This is a Mercury II Model CX half-frame 35mm camera made by the Universal Camera Company out of New York, NY. The Mercury II was an update to the original Mercury Model CC that added support for normal 35mm film rather than the proprietary Univex film used in the original. Both Mercury cameras were unique in that they used a rotary focal plane shutter that allowed it to reach a maximum shutter speed of 1/1000 second while keeping costs low.

Film Type: Half Frame 135 (35mm)

Lens: 35mm f/3.5 coated Wollensak Tricor 3 elements

Lens Mount: Mercury Screw Mount

Focus: 1′ 6″ to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Viewfinder w/ Parallax Hash Marks

Shutter: Rotary Metal Focal Plane Shutter

Speeds: T, B, 1/20 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Mercury Flashbulb Hot Shoe, synced at all speeds

Weight: 535g (body only), 576g (w/ lens)

Manual: http://www.butkus.org/chinon/univex/mercury_ii/mercury_ii.htm

December 2019 Update:

This month marks the 5th anniversary of this site’s first camera review. To commemorate this milestone, I’ve gone back and updated some of the site’s very first reviews, including this one for the Mercury II. Although that original review contained a lot of great information, my style of writing has changed dramatically over the past 5 years, so what follows is an updated review.

Most of the information from that original review is still present, with some additional historical information, more artwork, all new images of some later Mercury II cameras that I acquired after that original one, and two new galleries.

History

The Universal Mercury’s history is about as interesting as it’s design. The Universal Camera Corporation (sometimes also referred to by the name Univex) was founded in 1932 in New York City. They made a variety of lower end cameras that used a proprietary Univex film.

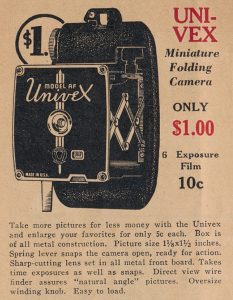

Their best selling camera was the all plastic Univex Model A which sold new for 39 cents. A more advanced model, called the AF sold for a mere dollar with new rolls of film only costing 10 cents. Universal wasn’t known as either a high quality or innovative company, and while their products weren’t bad, there were many other alternatives for consumers to choose from.

In the 1930s, photography was still a rather expensive hobby and there was a limited need for mid to high end cameras for the general public. For the professional photographer, more and more of the higher end cameras were coming from Germany. German manufacturers like Leitz and Zeiss-Ikon were able to build high quality cameras with interchangeable lenses, excellent fit and finish, extremely accurate optics, and shutters with speeds as fast as 1/1250 sec. American companies however, were still making cameras with shutter speeds that topped out around 1/200 – 1/300 sec. While this was fine for casual photographers, the more demanding professional was buying their cameras from overseas.

In 1937, Universal decided it wanted to design a new style of camera that could compete with the Germans, but at a much lower price. Brand new, a Leica III cost around $200 and a Contax III was a whopping $285 which after inflation, is $5162 today! As comparison, the Argus C3 sold for $25 making it one of the more popular American cameras of it’s day. Universal had the lofty goal of creating a camera that could compete with the Germans in terms of quality, but they wanted it to sell at the same price as the Argus.

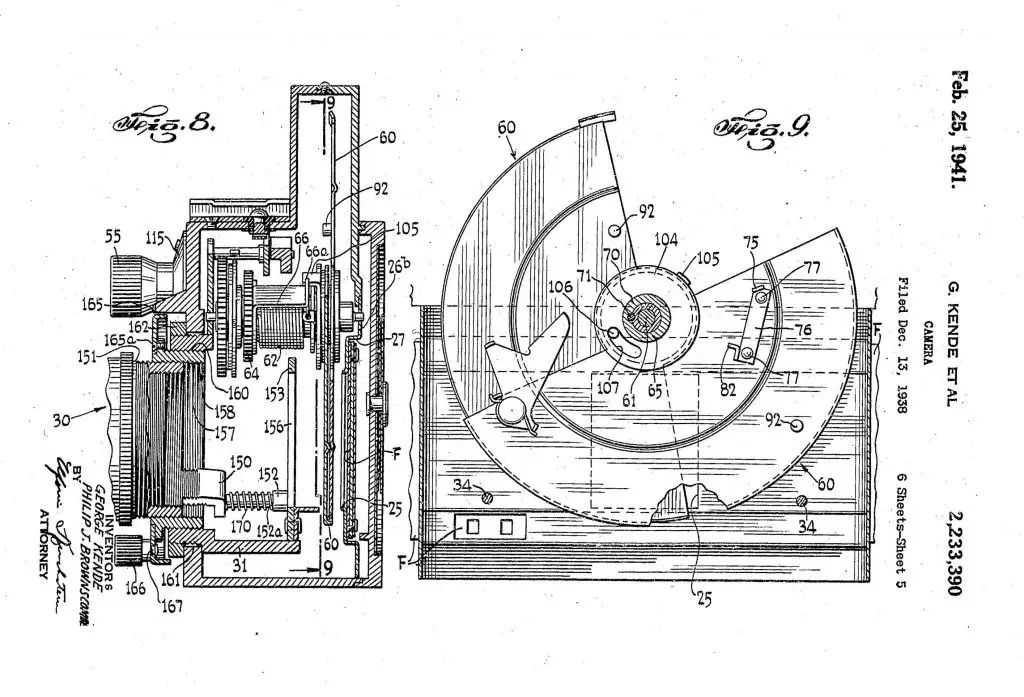

Since Universal wasn’t known as a premiere maker of cameras, they knew they wouldn’t have the design and production capabilities to make a Leica or Contax clone, so they knew they had to come up with a much cheaper way to accomplish their goals. For this, they turned to a man named George Kende. Two years prior, in 1935 Kende had designed an 8mm motion picture camera for Universal called the Univex Cine 8. The Cine 8 had a rotary shutter that could keep spinning at a fixed speed to allow the camera to shoot at a specific frame rate necessary for motion pictures. He used this knowledge of rotary shutters in motion picture cameras to design a spring loaded rotary shutter for Universal’s newest still camera. This rotary shutter is responsible for the large curved hump on top of the camera. This hump is not just for looks, it conceals the two discs that make up the rotary shutter.

Also like a cinema camera, the Mercury exposed images that were 18mm x 24mm instead of a double frame size like the Leica. In the years that would follow, the Leica’s image size of 24mm x 36mm would become the standard size for 35mm, and 18mm x 24mm cameras would be called “half-frame” cameras, but in the 1930s when the Mercury was first released, 18mm x 24mm was just the normal size. Compared to the images the Leica made, the Mercury would be able to shoot approximately double the number of exposures on the same length of film, all the way up to 65 frames.

The body of this new camera, which was going to be called the Mercury CC (for Candid Camera), would continue the rotary theme on the back of the camera with a very unique looking exposure calculator. This calculator was really just a spinning disc that the photographer would move to align several points to coincide with the type of shot they were aiming for, time of day, and type of light. This exposure dial is so complex that it takes 5 full pages in the camera’s manual to explain.

Another design element that Kende wanted in the Mercury CC was in-body flash synchronization. At the time, the most common type of flash sync was with external sync ports that required wires or cables to link the camera to an external flash. Kende’s design incorporated the very first use of a hot shoe on top of the camera that would directly connect the camera to the flash without any wires. The hot shoe on this camera was so well designed that Universal later added the feature to other cameras that they made. Hot shoes are still used to this very day as an attachment point between a camera and an external flash.

Finally, the last major obstacle to overcome in the design of this new camera was to build it cheaply so that Universal could hit its $25 goal. An added benefit to the design of Kende’s rotary shutter was that it had far fewer parts than the typical leaf or focal plane shutters used by other manufacturers. Aluminum and zinc die-cast parts were used to keep the number of precision parts to a minimum. This was done in an effort to employ unskilled laborers who would work for less. Universal outsourced the lens design and some of the accessories to other American companies to keep costs low. The lens was made by the American company Wollensak who already had knowledge of designing inexpensive interchangeable lenses.

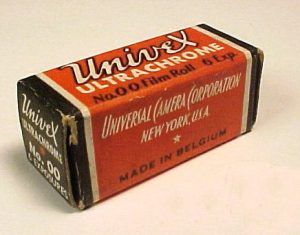

Universal had one more trick up their sleeve to guarantee profits. All Univex cameras used a proprietary “00” film that they sold exclusively for their cameras. The idea is similar to how smartphones are sold today. The camera would be sold as a “loss leader” with the expectation that people would have to keep coming back to buy film, which was where the company could continue to receive profits from.

In 1938, the Univex Mercury CC was released to an unsuspecting public who viewed Universal as a forgettable company that made cheap cameras. It boasted the worlds first rotary shutter in a still camera that could reliably hit speeds as fast as 1/1000th of a second. It was the only camera in the world with a flash synchronized hot shoe on the camera, and it was built in an attractive lightweight aluminum alloy body. As for the price? Universal delivered on their promise that this camera would sell for $25, which was equal to one week’s pay of the average American worker in 1939.

The camera was an immediate hit and sold well. Amateurs liked the camera because of its low price, and pro photographers liked it for its fast shutter speed and hot shoe flash synchronization. Universal’s profits soared 25% from 1938 to 1939, and the Mercury CC was mainly responsible for the entire Universal corporation’s profits.

Although the Mercury CC’s fastest shutter speed of 1/1000 tied it with the Leica III, the Contax II and III of the era boasted an even faster shutter speed of 1/1250. As a result, a higher end version of the CC, called the CC-1500 came out with a revised spring in the shutter that maxed the top speed at 1/1500 seconds to beat the Contax. The CC-1500 is a very rare camera as an estimated 3000 were made.

From 1939 – 1941, the Mercury CC continued to sell well and became one of the most popular American cameras of the day. But starting in 1941, the Universal corporation became involved in World War II and transitioned its manufacturing to making binoculars and other optics for the war effort.

Once the war was over, Universal decided to get back to making cameras, but they had a problem. Until this time, all of Universal’s cameras used a proprietary film that was unique to Universal cameras. This film wasn’t actually made by Universal, but instead by a company in Belgium who had the expertise of making film cheaply. After the war, getting anything made cheaply from a company in war-ravaged Europe would have been impossible, so Universal knew they had to redesign the Mercury CC to accept a different kind of film.

In the late 1930s and early 40s, 35mm 135 film was gaining popularity with still camera manufacturers. It was cheap, readily available, and well liked by the public. Universal knew that if they were to regain their status as a premiere camera maker, they needed to use 35mm film in the Mercury.

Universal’s proprietary film did not have sprocket holes and was narrower than 35mm film, so in order to incorporate the hardware to accept 35mm film, the entire body of the Mercury had to be redesigned. If you compare a Mercury CC with a Mercury II side by side, the Mercury II is both slightly taller and wider.

In order to stay in line with other 35mm cameras, the new Mercury needed to have an easy way to rewind the film, so a rewind knob was added to the top, and a film advance knob was added to the lower front of the camera. The larger body also allowed for a film reminder dial on the back of the camera, and a new frame counter which was separate from the shutter winding knob. To keep costs low, the new body was made from an aluminum-magnesium alloy as opposed to the all aluminum design of the Mercury CC.

The lens received some upgrades as well. Color photography was getting to be more common in the 40s, so the lenses available for the Mercury II received a new coating on the glass which made them less prone to flare on color film.