IMPORTANT: Pages dealing with whether a worker is an independent contractor or employee are currently under review in light of the High Court decisions in Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 1 and ZG Operations Australia Pty Ltd v Jamsek [2022] HCA 2. Please refer to these cases for the current approach to be taken in determining whether a worker is an independent contractor or employee.

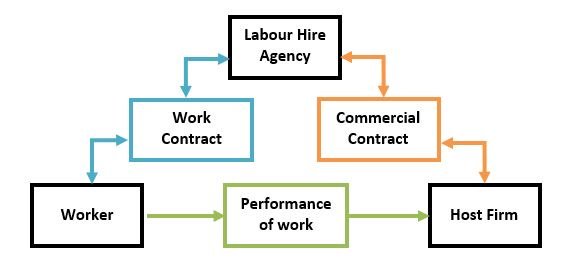

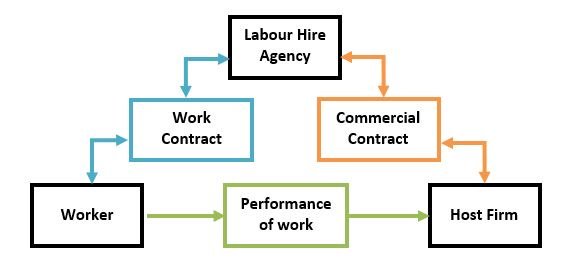

A labour hire worker is someone who enters into a work contract with a labour hire agency. The labour hire agency has a commercial contract to supply labour with a host firm. The worker performs work for the host firm. The host firm pays the labour hire agency, and the labour hire agency then pays the worker. The worker has no contract with the host firm and as a result cannot make an unfair dismissal claim against the host firm. An example of this is a nurse working for a nursing agency.

This arrangement is set out in the diagram below, adapted from Stewart’s Guide to Employment Law:[1]

Australian Courts have found that the interposition of a labour hiring agency between the agency’s clients and the workers the agency hires out to them does not result in an employee-employer relationship between the client and the worker. In those cases, in general, the hiring agency interviewed and selected the workers, and determined their remuneration, without reference to the client. Usually, a client requesting a worker with particular skills was provided with one, who may or may not have been ‘on the books’ of the hiring agency at the time the order was placed. The workers of such hiring agencies were usually meant to keep the agency informed of their availability to work, and in many cases were not to agree to undertake work for the client which had not been arranged or directed by the hiring agency. Equipment was either supplied by the worker themselves, or by the hiring agency, except for specialist safety equipment which the client often supplied. Dismissal of a worker was only able to be effected by the hiring agency. The client can only advise the hiring agency that the particular worker is no longer required by it. [2]

In some situations the labour hire agency and the host employer may be related entities. If this is the case, the host employer may be found to be the employer, regardless of the contract for work with the labour hire agency.

A number of cases have considered the manner in which the matters in s.387 of the Fair Work Act are considered in circumstances where an employer provides labour to a client and the client directs the employer to remove the employee from a site.[3] Labour hire arrangements in which a host employer has the right to exclude a labour hire employee from its workplace, are becoming a common part of the employment landscape in Australia.[4]

The reality for companies in the business of supplying labour is that they frequently have little if any control in the workplaces at which their employees are placed and the rights of such companies in circumstances where a client seeks the removal of an employee are limited. However, this is not a basis upon which companies in the business of supplying labour to clients can ignore their own responsibility for treating employees fairly when dismissal is the result of removal from a particular site, and the fairness of the dismissal is considered with reference to the matters in s.387 of the Fair Work Act.[5]

The refusal of a client to have an employee of a labour hire company returned to a particular site may form the basis of a valid reason for dismissal (based on capacity), however consideration would also need to be given to whether the employee could work at another site where labour is supplied by the employer.

Under the Fair Work Act the Commission has a the power to conduct inquiries and compel the production of documents.[6] This power can be used by the Commission to consider the terms of a contract to help determine the legal status of an applicant.[7]

Compel means to force or drive, especially to a course of action.[8]The applicant had been employed as a cleaner by Endoxos. Endoxos then restructured its operations so that the applicant and other employees would become contractors under a labour hire arrangement with another company. The applicant continued to perform the same work for Endoxos as a cleaner under its direction and control, using its equipment and in its uniform.

The applicant was held to be the employee of Endoxos.

The Full Bench overturned a finding that the applicant, who had entered into a contract with a labour hire company, was in fact the employee of the host employer to which the applicant had been assigned to perform work.

The Full Bench found that there was no contractual relationship between the applicant and the host employer.

The appellant in this matter was employed by MODEC Management Services, a labour hire company, to work at a BHP Billiton Petroleum Inc (BHPB) site. He was dismissed after BHPB exercised a contractual right to direct MODEC to remove the appellant from its site. At first instance the Commission held that the dismissal was not harsh, unjust or unreasonable.

The appeal was made on grounds that the Commission erred in finding the question of valid reason did not arise on the facts. The Full Bench granted permission to appeal as the appeal raised broader question regarding the obligations of a labour hire employer.

The Full Bench found that BHPB's instruction to MODEC that the appellant was not permitted to work on site represented a matter going to the employee's capacity to work. The issue required consideration under s.378(a) of the Fair Work Act to determine whether there was a valid reason for dismissal. The Full Bench held that the Commission erred in finding the circumstances of the dismissal did not give rise to a consideration of valid reason. The appeal was upheld and the matter redetermined. To be a valid reason the reason must be defensible or justifiable on an objective analysis of the facts. The Full Bench was satisfied that MODEC had a valid reason relating to the employee's capacity and only exercised the reason because it was genuinely unable to find suitable alternate employment for him. Having considered the s.387 factors the Full Bench held that the dismissal was not harsh, unjust or unreasonable and confirmed the Commission order dismissing the unfair dismissal application.

The applicant in this unfair dismissal application worked as a casual Machinery Operator at the Goonyella Riverside Mine for WorkPac, a labour hire company. WorkPac was directed by its client, BHP Billiton Mitsubishi Alliance (BMA), to remove the applicant from their site. When the applicant asked WorkPac why this was occurring, a WorkPac representative said that she did not know the reason, but that the ‘demobilisation’ was not related to the applicant’s performance. The representative also said that she would email a termination letter to the applicant. The applicant understood from this conversation that her employment was terminated. The applicant had no ongoing employment or income from WorkPac after that point.

The Fair Work Commission found that the applicant was dismissed when WorkPac complied with BMA’s direction to remove her from their site. The Commission considered whether WorkPac had a valid reason for the dismissal related to the applicant’s capacity or conduct. The Commission found that there was an inference that a conduct issue related to the direction to remove the applicant from the site existed, however WorkPac failed to make any enquiry of BMA to establish the reasons. On the balance of probabilities the Commission found the reason for the direction to remove the applicant from the site was related to conduct.

The Commission found there was no valid reason for the removal of the applicant from the site leading up to the dismissal, and that WorkPac failed to consider alternative assignments before terminating the applicant’s employment. The Commission found that the dismissal was unfair. The Commission held the provisional view, with some reservations, that reinstatement was an appropriate remedy. The Commission provided an opportunity for the parties to consider their positions in relation to reinstatement.